Black History Month 2020

In the final week of Black History Month 2020, we’re celebrating Black civil rights heroes who have transformed the landscape and the law on human rights in the UK, all while facing down rampant racism and fighting for their own basic freedoms.

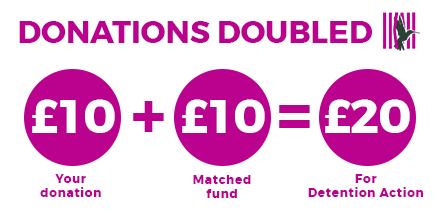

DONATIONS DOUBLED NOW!

Urgent LocalGiving is matching all donations up to £75 to fund our response to the COVID crisis in immigration detention centres.

Last week, inspectors yet again uncovered inhumane and unsanitary conditions in UK detention centres.

We have our work cut out and we have to act fast – the matched fund could run out at any time.

By fighting for racial equality, refugee rights, LGBTQI+ equality, and so much more, these influential figures have strengthened the principles of freedom and equality for all – making the UK a better place for everyone in the process.

There is so much work still to do, and we will draw our inspiration from those who have come before.

We began in Part 1 by looking back into history at early wins for freedom. In Part 2 we took a look at post war Britain, and the attempt to rebuild for a better world. Now, in Part 3, we look at the 1960s and 70s – a time of vital importance to the UK’s civil rights struggle.

In this series:

Part 2: Post war Britain: Rebuilding for a better world

→ Part 3: Speaking truth to power in the 1960s and 70s

Part 3: 1960s and 70s: speaking truth to power

The Bristol Bus Boycott

The 60s were a hugely important time for the UK’s civil rights struggle , beginning with the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963.

Members of Bristol’s Black community were aware of a “colour bar” in the Bristol Omnibus Company’s hiring policy, that was even backed by the company’s trade union.

To highlight this injustice, Guy Bailey went for an interview. He was sent home before he even got into the room. Armed with proof of discrimination, activists united and organised a boycott of the city’s buses. The boycott began in the Black Community, but people managed to galvanise some of their non-Black neighbours, who also joined the protest.

After four months the bus company caved to protesters’ demands.

The Bristol Bus Boycott brought racial discrimination into focus, and is credited by many as having helped to enable the UK’s first racial discrimination laws a few years later. It also emboldened the struggle of other workers across the UK.

Three years later, Asquith Xavier was appointed as the first non-white guard at Euston station after a campaign against their unofficial “colour bar”. His campaign led to a strengthening of the 1965 Race Relations Act, which was extended in 1968 to make it illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services to people because of their ethnic background.

1964: Paul Stephenson helps to desegregate pubs

Paul Stephenson – one of the leaders of the Bristol bus boycott – made national headlines when he went to court to protest being forced to leave a pub because he was Black.

Upon entering the Bay Horse pub, Stephenson had been told by the owner that Black people were a nuisance and he needed to leave. Stephenson held his ground, and eventually police officers were called. Stephenson was arrested and held for refusing to leave licensed premises.

At Stephenson’s trial, all eight police officers gave their account of arresting him at the pub, branding him “aggressive”. Despite this attempt to smear him, another witness had been drinking in the pub and corroborated Stephenson’s account of events. He was acquitted and awarded £25 in costs.

Stephenson’s stand against legally mandated racism once again received national attention; Prime Minister Harold Wilson even sent Stephenson a personal telegram promising to change the law. One year later, the UK’s first Race Relations Act was brought in, which outlawed discrimination in public places.

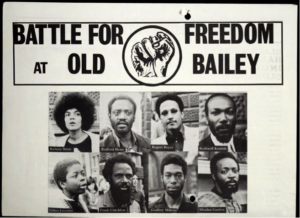

1970: Darcus Howe and Althea-Jones Lecointe represent themselves in the Mangrove 9 trial

Howe and Jones-Lecointe were two of nine defendants accused of inciting riots after protesting in defence of the Mangrove restaurant, a much-loved Caribbean restaurant in Notting Hill frequented by many members of the Black Community, including celebrities like Jimi Hendrix, Bob Marley, and Diana Ross.

People described the Mangrove as a sanctuary, but before long the owner Frank Crichlow was hounded by the local council who rescinded his late-night license. Police began harassing Crichlow almost nightly, often coming in to raid the property.

In 1970, the newly formed UK Black Panthers helped to organise a protest to defend the Mangrove. Around 150 peaceful protesters were met by over 600 police. Many of the witnesses testified that violence was incited by police, but nine protesters were arrested for inciting riot and affray.

Howe and Lecointe-Jones chose to represent themselves to expose the politically motivated nature of the trial, and appealed to ancient rights enshrined in the Magna Carta to demand their right to be tried by a jury of their peers, who in this case would be black people.

This was dismissed, but each defendant exercised their right to dismiss seven jurors, thus ending up with two Black people on the jury. All nine were acquitted of the principle charge, while five were acquitted of all charges.

In a historical move, the Judge was also forced to admit evidence of racial hatred on part of the police. The trial brought the fight against police racism into the national consciousness – defendant Frank Crichlow said it “put on trial the attitudes of the police, the Home Office, of everyone towards the Black community.” The Mangrove 9 proved it was possible to take on the authorities and win, inspiring anyone who wants to speak truth to power.

In this series:

Part 2: Post war Britain: Rebuilding for a better world

→ Part 3: Speaking truth to power in the 1960s and 70s

DONATIONS DOUBLED NOW!

Urgent LocalGiving is matching all donations up to £75 to fund our response to the COVID crisis in immigration detention centres.

Last week, inspectors yet again uncovered inhumane and unsanitary conditions in UK detention centres.

We have our work cut out and we have to act fast – the matched fund could run out at any time.